On Profanity

Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, Smokey and the Bandit, "Guess This Is Kaput," Gillian Welch, and Steve Earle.

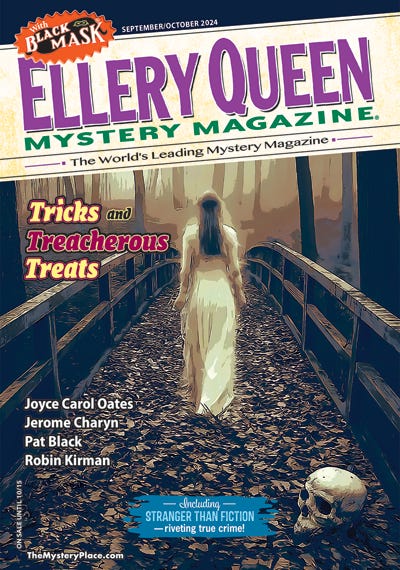

A really wonderful feeling comes from landing a story in a place you’ve been trying to publish for years, usually equal parts disbelief and elation. I felt that way when Andrew Tonkovich called me about a story I’d sent Santa Monica Review, to this day the first and only time the editor of a literary magazine has called me with an acceptance. And I felt that way when Janet Hutchings emailed to say she wanted “Hell-Bent for Leather,” which is in the new issue of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.

I’d been trying to get into Ellery Queen for years. I think it’s safe to say it’s the highest profile crime genre publication in the world, or at least in the running for that superlative. I send them everything that seems like it would fit, despite the fact my sensibility doesn’t always suit theirs. Their tastes lean more toward the cozy than they do toward noir, and noir or noir-adjacent is sort of my sweet spot.

But I’ve learned a lot from submitting to them, including a lesson about the value of profanity in art, or lack thereof. Not I hadn’t learned this lesson before. Once, in a workshop, someone told me one fuck per 20 pages—as opposed to one or two per page—was sufficient.

But what about Larry David’s advice from Curb Your Enthusiasm: “So you throw in a fuck, you double your laughs.”

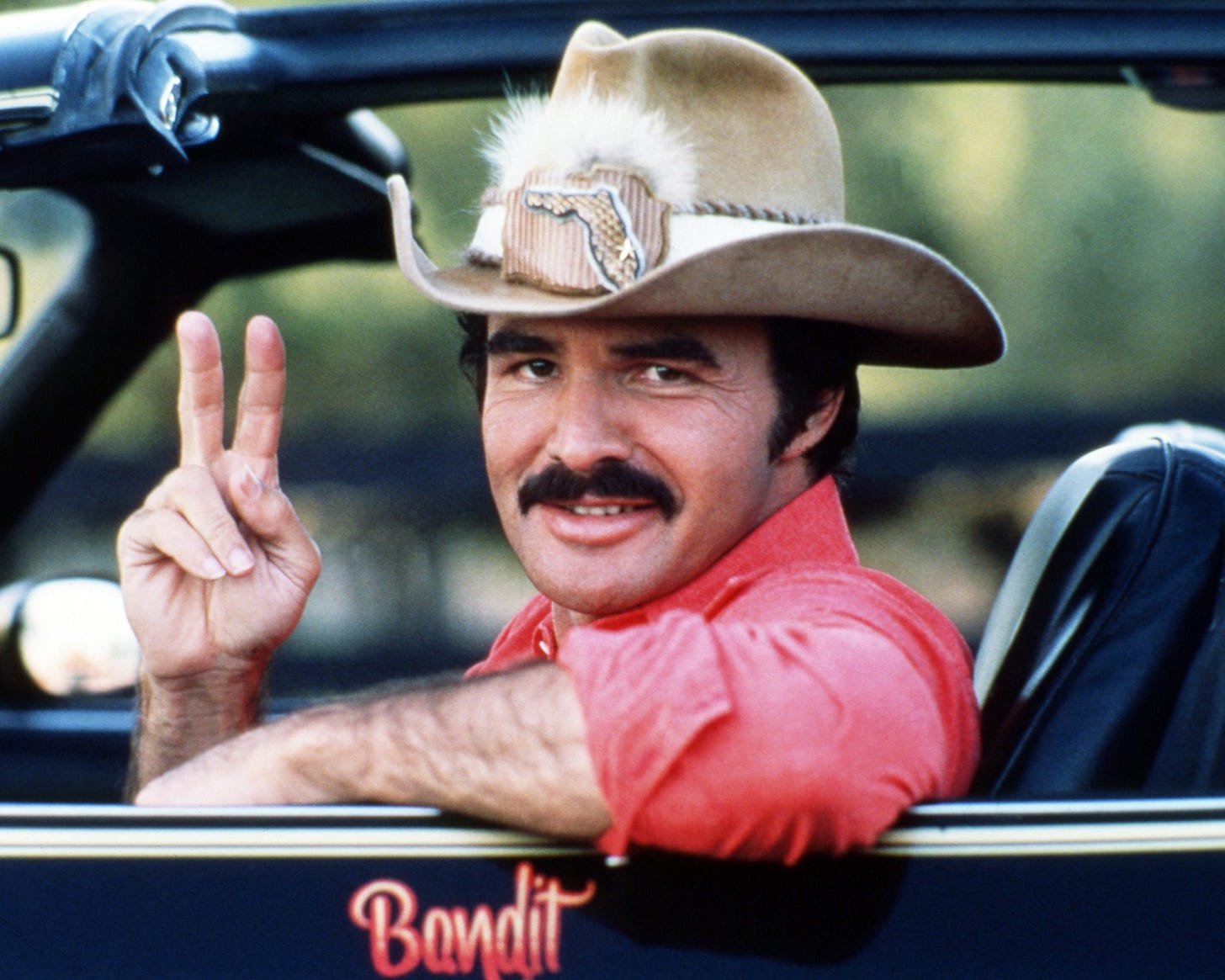

I learned to swear in the third grade. My parents rented Smokey and the Bandit, which I loved. And I found the profanity only added to the humor. First at home, then the next day at school, I kept repeating all these exciting, funny new words.

On the drive home, after a conversation with my teacher, my dad explained that certain words were only supposed to be used in certain places, maybe my first real lesson in context, which as the first line of Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn would have it, is everything. Years later, teaching writing at community college, that concept was a cornerstone of the curriculum: know your audience. There’s nothing wrong with text language: LOL, etc. It’s appropriate with friends on a Friday night, but not in a paper on James Baldwin or when writing a nursing exam.

I think many of us in the crime genre pride ourselves on a certain sense of realism in our writing. I like the unadorned quality of a lot of noir and detective fiction. Of course, that can veer too much toward the sentimental. A world in which there are no good people, in which everyone is on the take or a grifter with no inherent goodness isn’t any more realistic than a world in which everyone is on the up and up. The inversion of the pollyanna cliche is no more true than the cliche itself. Similarly, when it’s not working, Hemingway’s tough, unsentimental prose can seem very sentimental.

A few years ago I wrote a story called “Guess This Is Kaput.” It’s a story about a kid who moves to Oklahoma with his dad after his mom dies. He hates his dad because his dad had been having an affair with one of the mom’s friends. The kid is wracked with guilt because losing his mom was too much for him to bear, so he checked out, smoking a lot of weed in the garage, rather than saying goodbye when she was on hospice.

All that is backstory, but it’s important backstory. He’s taken up with a woman in Oklahoma. It’s not especially serious. Still, when she tells him her ex who might not really be an ex is getting out of prison, instead of doing the sensible thing and leaving, he agrees to go with her to pick the guy up from the state penitentiary.

And all that backstory is important because that’s the reason he does that. He doesn’t want to fail her the way he failed his mom.

And if he doesn’t do go with her to pick up the ex, well, there’s no story.

The first draft was peppered with f-bombs and other vulgarities. The story ends—spoiler alert—with the characters freebasing crank, so that vulgarity was appropriate to world, milieu, etcetera. And while I knew the drug use and some of the other elements of the story meant it likely wasn’t ideal for EQMM, it was a noir story, so genre-appropriate. So, I cleaned up all the f-bombs and sent it in.

They didn’t publish it. It eventually got picked up by Xavier Review. It’s a good story, probably one of the better things I’ve written, at least in my opinion. But it wasn’t right for EQMM. Still, a funny thing happened after I sent it to them. I was thinking I’d keep the f-bombs in the version I was sending to other publications, but when I looked back at the story, I realized I didn’t need any of them. The story was better without them, creepier, more unsettling. It left more to the imagination, and more was buried in subtext. And in fiction, regardless of genre, subtext is everything, too.

Not that I’m opposed to swearing. A band I’ve been gigging with, the High Desert Playboys, covers Gillian Welch’s “Everything Is Free,” a song she wrote about file sharing that’s just as apropos in the streaming era. The song ends with the line, “If there’s something you want to hear, you can sing it yourself.” The singer in this band changes a couple syllables, “If there’s something you want to hear, fucking sing it yourself.”

I’d say the profanity is appropriate. It heightens the feeling of abjection and gets at the helplessness and the rage simmering underneath it. We turn the song into a noise jam and let it fall apart while torturing our instruments. Of course, he doesn’t do that when we’re performing at family friendly venues. Again, context is everything.

One of my favorite songwriters, Steve Earle, was kicked off a tour with the legendary Del McCoury, who he’d recorded an album of Earle’s bluegrass songs with, because Earle swore too much on stage. Maybe that’s silly: who would be hung up about swearing at a rock and roll (or a bluegrass) show? Or maybe it’s immature, childish of Earle to cuss so much when he knows it upsets people. Either way, it’s hard to deny certain words still have the power to shock or to offend.

But it’s also like shouting at people in a quiet room. At least in art, we want to feel what’s at stake emotionally for the characters, and we do that by sinking into a story. And profanity can keep us from sinking in. However much he swears onstage, Earle doesn’t cuss very often in his songs. And while I’m generally pro-profanity, I think limiting how I use it has generally made my stories better.

Great post -- and congrats again on landing in Ellery Queen! I'd forgotten about the Steve/Del McCoury thing (I was, of course, very much on Team Earle at the time). I learned over the years how, in both teaching and my white-collar work, a well-time F-bomb can really get the point across. But they're like 7th chords in that you can't overuse them. ;-)

One "fuck" per 20 pages?! Fuck that. ;)